From the ECONOMIC POLICY

INSTITUTE

Income Picture

August 28, 2007

Poverty, Income, and Health Insurance trends

in 2006

by Jared

Bernstein, Elise

Gould, and Lawrence

Mishel

Reflecting the fifth year of an economic expansion, the percent of

the nation in poverty fell last year, and the income of the median

household grew (after inflation) by about $360, or just under one

percent (0.7%), according to data released today by the U.S. Bureau of

the Census. This is the second year of real income gains for the

median household, and the first significant decline in poverty since

2000.

While both poverty and income have improved over the last few years,

it is disappointing that despite low unemployment and strong

productivity growth, these measures of living standards have yet to

recover to their levels of the previous business cycle peak in 2000.

In that year poverty was 11.3%, compared to 12.3% in 2006, an increase

in the poverty rolls of 4.9 million persons, including 1.2 million

children; median household income in 2006 was $48,201, about

$1,000 dollars (-2.0 %) below its 2000 level (in 2006 dollars). In other

words, economic growth over the last six years has totally bypassed the

typical middle-class household.

One negative trend persists: The share of Americans without health

insurance coverage once again increased, from 15.3% in 2005 to 15.8%

last year. There were 47.0 million uninsured Americans in 2006, up

2.2 million since its 44.8 million level in 2005. Since 2000, the

share of the population without health coverage has increased 2.1

percentage points, an increase of 8.6 million uninsured Americans.

Earnings of full-time workers

Reflecting the narrow extent to which the growing economy has been

showing up in the paychecks of many working-age households, median

annual earnings by full-time, year-round workers fell in 2006, for the

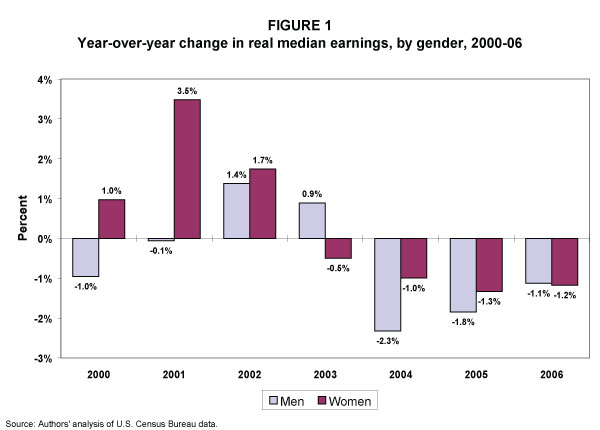

third year in a row, down about 1% for both men and women. Figure

1 shows annual earnings changes for these workers, who are, by

definition, working year-round. Despite their efforts, men’s

earnings have fallen 0.5% annually from 2000 to 2006, while those of

women were rose only 0.2% annually (and, as noted, have fallen steadily

since 2004).

The decline in median earnings in tandem with higher household income

at the median suggests that it was more hours worked and more people

working, and not higher wages that generated the income growth for

middle-class households last year.

The unequal distribution of growth between profits and compensation

is playing a critical role in this result. Our research on

corporate sector profits reveals that, had profits grown at the same

rate as labor income between 2005 and 2006, then compensation would have

been 1.1% higher for all workers: that is, the earnings declines among

male and female full-year workers last year can be accounted for by a

profit squeeze on wages.

Note also that this very weak wage performance has occurred while

productivity growth increased 3% per year (2000-06). While

economists and policy makers typically stress the positive performance

of such indicators as productivity, GDP, or low unemployment, these

earnings results clearly reveal that positive macro-conditions have not

led to wage growth for typical full-year workers, as customarily had

been the case.

Income inequality

The main reason for this disjuncture between productivity and

compensation is the increase in economic inequality. When growth

is unequally distributed, positive indicators like faster GDP or

productivity growth create only the potential for increased

living standards. In a climate where too many workers lack the

bargaining power they need to claim their fair share, we expect to see

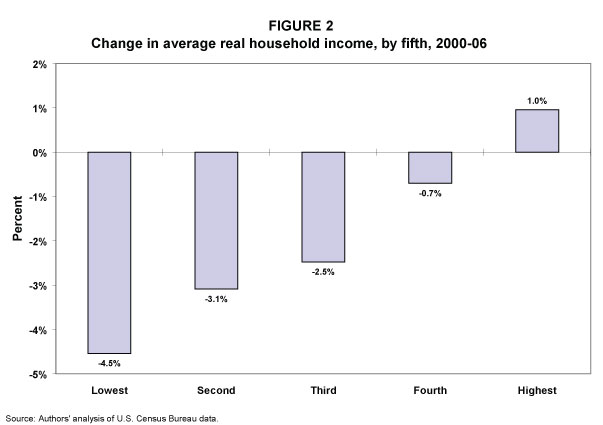

patterns like those in Figure 2, which clearly shows how income

gains have been skewed toward those already at the top of the income

scale.

Between 2000 and 2006, the average income of the lowest fifth is down

4.5%, the middle fifth is down 2.5%, and only the top fifth is up, by

1%. Similarly, today’s report revealed that the share of income

going to the top fifth of households was 50.5%, the highest share on

record going back to 1967. The middle-income share was 14.5%, the

lowest on record. The bottom income share has been 3.4% since

2003, also an historic low.

Large losses for African

American households

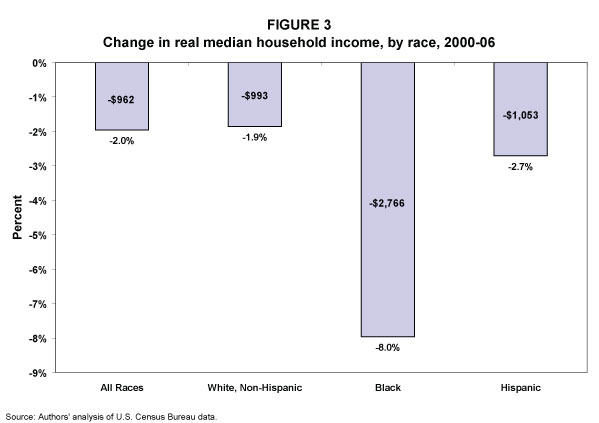

Examining income changes for different ethnicities reveal important

disparities in economic outcomes. African Americans, whose median

household income was unchanged last year (up a statistically

insignificant 0.3%), have experienced particularly large losses since

2000 (see Figure 3), posting a loss of 8%, or about $2,800.

Working-age households

The median income of working-age households (those headed by

someone less than 65) was up 1.3% last year, the first year of income

growth since 2000. (This was driven exclusively by younger people, ages

15-24. Households headed by persons 25-64 saw only insignificant gains.1)

Even so, the median income for these working-age households is down 4%,

or about $2,400 lower than in 2000.

Historical landscape

How have poverty, income, and inequality developed over this business

cycle compared to earlier ones? Since the 1970s, poverty rates

have been largely insensitive to economic growth, due to factors ranging

from slower and less equally distributed growth, higher average

unemployment, diminished wage growth at the low end of the pay scale,

and the greater share of one-parent families, who are more vulnerable to

poverty.

These trends were reversed, however, for a period in the latter

1990s, as uniquely low unemployment, strong job creation, and faster

productivity growth enabled more workers to claim a larger share of the

growing economy.

Median household income, for example, rose less than 1% between 1967

(earliest available data) and 1995, before speeding up to an annual rate

of 1.9% (1995-2000). For minority households, median income growth

in the latter 1990s was especially strong, as was poverty reduction,

with the median income up 3.4% for African Americans and 5.3% for

Hispanics. Poverty for African American children fell an

unprecedented 10.7 percentage points, compared to 2.1 points for white

children.

The recession starting in 2001 halted these gains, and—as is

virtually always the case in a widespread downturn—poverty began to

rise and household incomes fell across the income scale, particularly

for working-age households (though high-income households were hit hard

by large capital losses in the early 2000s).

But when the recession ended in late 2001, poverty and median income

did not improve. To the contrary, both have worsened since then, as the

so-called jobless recovery made it too difficult for working

families—those that depend on paychecks, not stock portfolios—to

find enough employment in decent quality jobs.

Immigration's impact on

poverty

Some analysts have argued in the recent immigration debate that overall

poverty trends are now largely driven by a larger immigrant population.

The implication of this view is that poverty rates would improve and the

economy grows if immigration was diminished or comprised of more highly

skilled workers.

The data, however, do not bear out this view. While it is true

that immigrants have higher poverty rates than natives (11.9% vs. 15.2%

in 2006), immigrant poverty rates have fallen more quickly than that of

non-immigrants in recent years. This positive development over

time has to be balanced against the impact of a larger immigrant

population.

Last year, for example, immigrant poverty fell 1.3 percentage points,

compared to the statistically insignificant 0.2 percentage point decline

for non-immigrants.

Another way to demonstrate this point is to ask what the overall

poverty rate would have been in 2006 if the shares of immigrants and

non-immigrants were frozen at the population shares of an earlier

period. The difference between this simulated rate and the actual

rate allows us to determine any pressure on poverty rates due to more

immigrants. What we find is that if the immigrant share of

the population was currently the same as it had been in 1993 (the first

year Census poverty files include these data), the national poverty rate

would be essentially unchanged (only one-tenth of a percent higher).

Health insurance

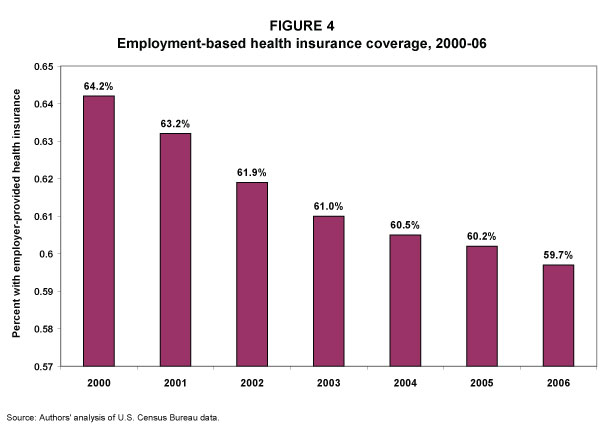

The decline in insurance coverage in this country can be attributed to

declines in private coverage, particularly employment-based health

insurance. There is evidence of further unraveling of the

employer-based system:, the share of persons covered through work

(either their own or a family member’s employer) declined for the

sixth year in a row. As shown in Figure 4 below, employment

based coverage was 59.7% in 2006, down from 60.2% in 2005 and a total of

4.5 percentage points since 2000.

The declines in employment-based coverage were particularly striking

for dependents, as children under 18 without such coverage declined 1.2

percentage points over the year, continuing an annual decline since 2000

of 6.2 percentage points, from 65.9% to 59.7%. Public insurance

has not been strong enough to offset these declines, and so the percent

of uninsured children rose for the second year in a row. In the last two

years, the number of uninsured children rose by 1 million, from 7.7

million in 2004 to 8.7 million in 2006.

—Research assistance by James Lin.

|

Trust the Trend

The official U.S. poverty measure is roundly, and justifiably,

criticized by poverty analysts of all political stripes.

For details see this

testimony, but the current measure is generally agreed to be

both out of date and not an accurate reflection of who is and

isn’t facing material hardship.

But that by no means should lead analysts and policy makers

to dismiss today’s findings.

The most important information in this regard is not the

poverty level, which is likely inaccurate, but the trend in

poverty rates, which does provide an accurate depiction of the

extent to which economic growth is reaching low-income families.

The fact that poverty fell last year indicates that such

families made some economic progress. The fact that the

rate is still well above its 2000 level shows that little

progress has been made.

One reason to trust the trend is that much better measures of

poverty, developed by the Census Bureau to update the official

measure, closely track the trends in the official rate.

Census publishes 12 such measures, all based on variations in

recommendations made by the National Academy of Sciences.

These measures have not yet been updated to 2006, but their

average for 2005 was 13.4%, compared to the official rate,

12.6%. The average of the measures that most closely

reflect the NAS recommendations was 13.9%.

Most importantly, the trend in these more-accurate measures

moves with the official rate. For example, the Census

alternative measure that we judge to most-accurately reflect NAS

recommendations rose 1.3 percentage points since 2000, the same

growth rate of the official rate.

In short, the fact that the official poverty measure is one

percentage point above its 2000 level is stark evidence of the

extent to which the benefits of growth since then have not been

broadly shared.

|

Endnote

1. This observation is based on data

published today showing insignificant gains for each age category within

the 25-64 group. We cannot determine whether the change for the

group as a whole would be insignificant.

[Media Kit]

To view archived editions of INCOME PICTURE, click

here.

The Economic Policy Institute INCOME PICTURE is

published upon the annual release of family income data from the Census

Bureau.

EPI offers same-day analysis of income, price,

employment, and other economic data released by U.S. government

agencies. For more information, contact EPI at 202-775-8810.

|